How did you arrive at quilting, Luke? You are from the South, a bastion of American quilting, especially African American quilting, such as with the Gee’s Bend collective. You also have formal art and architecture training. How did your upbringing and training inform your turn toward quilting? Are you still based in the South? How did you learn to quilt?

I came to quilting through my gateway craft of Knitting. I had an alternative upbringing, bouncing between boarding schools and parents, so craft, which represents safety and comfort, played a massive role in my upbringing. I felt better when I could make the objects I needed to exist. I studied fine art and architecture and then left after that to pursue quilts as a profession, which is a combination of both. I am now living in LA, but my heart is always based in the South, for better or worse. I learned to quilt by trial and error and research.

Quilting has a heavily gendered history. How do you interact with the traditionally feminine nature of quiltmaking? Is it something you think about?

I do think about it a lot. Mostly, I say to anyone who asks that it’s paramount to the history of quilting to recognize why it’s a historically gendered medium. Women had to gain agency over time within the communities that generated quilting as a medium [aka as something more than just a function item, aka “blanket.”] As quilting came to popularity in America and, to a lesser extent, in Europe, women were hired to create these objects and, as a result, could gather and own the income generated from the sales, which was largely unprecedented. PLUS, of course, the gender of homemaking and the domestic falling largely to the feminine in middle to lower-income households. Contemporarily, it’s not the same, but we don’t live in a history-free vacuum, so the reference is vital as modern makers make.

What is quilting’s relationship to the environment? American quilts have historically been made of scraps or recycled fabric—something we would now call environmentally friendly but was purely practical in the 19th century.

Most of the history of quilting as we know it is one of expense rather than frugality. If one needs more time or money to cut down the costly fabric, sewing it back together painstakingly isn’t a great use of time or resources. The wealthy [or the perceived rich] used quilts to show leisure time and affluence. This is, of course, only true in places like Gees Bend and the fringe communities trying to make a function from everything available. You can see the difference aesthetically between the two types of quilts. The functional ones used ties, extensive panels, and large stitches to finish the work, and the decorative ones used smaller pieces and decorative stitches. Even the quilts made of scraps or feed sacks came from households that could afford the fabric or the farm in the first place. Today, quilting as a medium is also one of the upper-middle class primarily. To make a quilt, it costs roughly $200 in materials before the 100s to 1,000s for machines, scissors, tables, etc., so if someone wants/needs a blanket, Target is an infinitely better place to get a quilt than make one. Most contemporary quilts are made with new fabric, a practice not born of environmental awareness but rather convenience for the maker. I use primarily used and reclaimed textiles, and others like me use that as a practice, but it’s the exception and always has been.

I was interested in the phrase “textile language,” which you mention in the bio on your website. Could you expand on that? How do your quilts relate to the community? Quilting often has communal aspects—such as the quilting bee—do you feel this coming through in your process or artworks?

The most significant part of the community I work with is nostalgia for blanket utility and specific fabric. Using a medium that is understood tacitly allows a different engagement than most standard art mediums, so “textile language” is the texture and nostalgia for the print or the item’s usage in addition to the usual composition and color/value/hue. I feel I have more attributes to use as the language of my art than most other mediums; pulling from the experience of the viewer, I get to have a dialog about their experience as a human in a body with the warmth of a bed and the textures of the fabric as well as their experience over time with specific material like the sheets their grandma had to the weave of their favorite shirt to just a character they recognize from their own life experience. So my work isn’t implicitly communal in the traditional ways of having lots of hands make it or a group contribute, but more so in the communal experience of being alive.

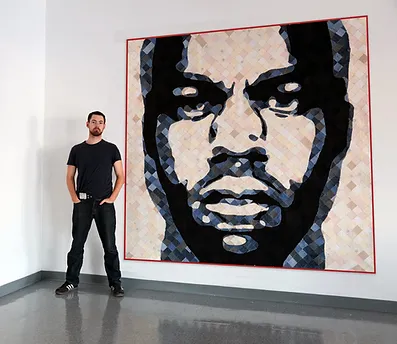

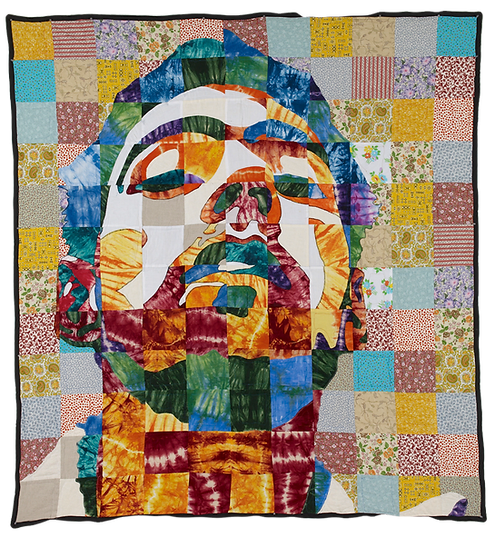

I’d love to hear more about your style of quilting. I might call it quilt portraiture— an unusual use of quilts and celebrated modern quilts such as those from Gee’s Bend tend to be abstract/geometric. The backgrounds of several of your quilts feature traditional patterns/blocks, with a modern portrait on top. The portraits are almost cel-shading or poster-like, which is probably the most efficient way to work with the medium. It also signals interestingly to modern animation/comics/digital illustration. And I saw one quilt in which you used an optical technique taking advantage of foreshortening—like the skull in Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors. This hasn’t precisely shaped into a question, but please talk about your art! How do you characterize your art?

I used to call my quilt style “Pop-art Quilting,” asking folks to recognize the history of portraiture in art and specific pop art. Lately, however, I have been going away from that term since I am not working on aesthetics and concepts of the 50s-70s. However, many underlying notions exist, like elevating the daily experience and the “everyman” as subject and viewer. My most giant soapbox over the past few years is that: “quilts are sculpture.” That is why I am working with an anamorphic perspective: to force the viewer to move around the object and direct the experience to that of sculpture, which has to be perceived from multiple vantage points to be understood fully.

What does modern quilting mean to you? What is the future of quilting?

“Modern” is a hard word to quantify since 100 years ago, it was what all art made was called, and now that art is old. Haha. Not to be pedantic, to say that in quilting, like the rest of “art,” there is a personality crisis between craftmanship and the big white room museum/gallery concept. In the future of quilting, I hope to be like a tributary into the river of “art” so we can all understand art in our experience rather than just in rooms that are designated art spaces.

Quilts seem to work very well as a physical metaphor—for building knowledge, relationships, a self, etc. The idea of stitching parts together into a greater whole is widely significant. Does your medium carry symbolic significance for you?

100%, I use the language of discarded clothing and bedding to enhance the experience of a human today. For now, building something from parts discarded into a function or expertise is quilting a metaphor for sure!

How do you view the art-craft divide? What implications does it carry for your work? Does your work comment on this? What happens when you change an object’s function with a well-known historical function?

Unfortunately, this is more a product of the value gatekeepers than a fundamental divide. Like Debeers has to hide diamonds to keep the value of their inventory up, the world of selling art has to strongly dissuade new mediums not to change the market saturation and the importance of blue-chip paintings. I have done a bunch of work about this conversation. I am happy to share more on this and anything you need/want.

You can find more info about Luke Haynes on his website Here: https://www.luke.art/